My friend Faye and I have now been pedalling, or rather pushing, uphill for 11 hours. We’ve ascended 2,550 metres over a painstakingly slow 25km and we’re not done yet. The incline steepens, and steepens until both of us are wedged firmly into the hillside. We appear like frozen statues, every muscle contracted and held in position, hands gripping the brakes, doing all we can just to stop our bikes from rolling backwards. Yet still our feet begin to slide slowly downward on the loose gravel – losing us precious centimetres in the fight.

I’m trying a new strategy to make progress. This involves resting for ten seconds, before pushing for three steps and trying my best not to wet myself under the strain. Alas, the strategy soon becomes futile. The bike skids sideways, I slip and land in a heap with bike and bags on top of me. ‘Arrrrrggghhhhh!!!’ I scream, lying on my back and staring at the cloud spattered sky.

‘You alright?’ comes a distant call from Faye, who is now above me on the slope. I don’t move, I just sigh and lay there wondering what on earth I am doing here. In the end I accept that I cannot push the fully loaded bike any further. My arms and back are screaming at me and so I settle for an extreme version of PE lesson shuttle runs. I take my bags off the pannier racks, and ferry bags and bike up the hill separately in stages.

“I settle for an extreme version of PE lesson shuttle runs. I take my bags off the pannier racks, and ferry bags and bike up the hill separately in stages.”

We reach a small plateau and both flop on the floor to rest a while, mentally preparing to take on the final, equally steep, section of climb. Faye looks at me, and does a double take. ‘Oh god… mate.’

‘Whaaat? Whasss up?’ I slur in reply.

‘You look ruined. I’ve never seen you so white!!’ Which is funny because I was just beginning to think the same thing about Faye.

‘Well, if I look even half as bad as you do, we’re in big trouble.’ I retort.

We laugh. All we can do is laugh, delirious, exhausted sweet delicious laughter. For the final ascent we hatch a cunning plan. Both of us work together to push just one fully loaded bike up the slope at a time. Bernard (my bike) goes up first, followed by Gustavo (Faye’s bike). The bikes now feel floaty light with four arms on them as opposed to two – we begin to let out war cries, spurred on by faster progress up the climb.

At last we shove the second bike the final few centimetres over the the crest of the final hill, where we are greeted by the most majestic scene. We are now 3,200 metres high. The sun hangs low in a pale blue sky – its rays shooting off in a hundred different directions like a recently exploded firework. Mountains upon mountains are silhouetted against the warm evening glow. Some nearby and intimidating, others just ghostly outlines in the distance. And then there they are: two gigantic condors, black bodied, huge wings – just floating, right above our heads.

“We are now 3,200 metres high. Mountains upon mountains are silhouetted against the warm evening glow.”

Our jaws drop to the floor and we take a moment to look at one another, before returning our gaze to the birds. There is no point in speaking as the wind is so strong up here that we wouldn’t hear one another anyway, but we don’t need words. There are no words for this. There is no one here – goodness knows the last time when there was someone here. It is as if the condors know. As if they’ve been watching all day and they’ve popped out for an evening flight, especially for us.

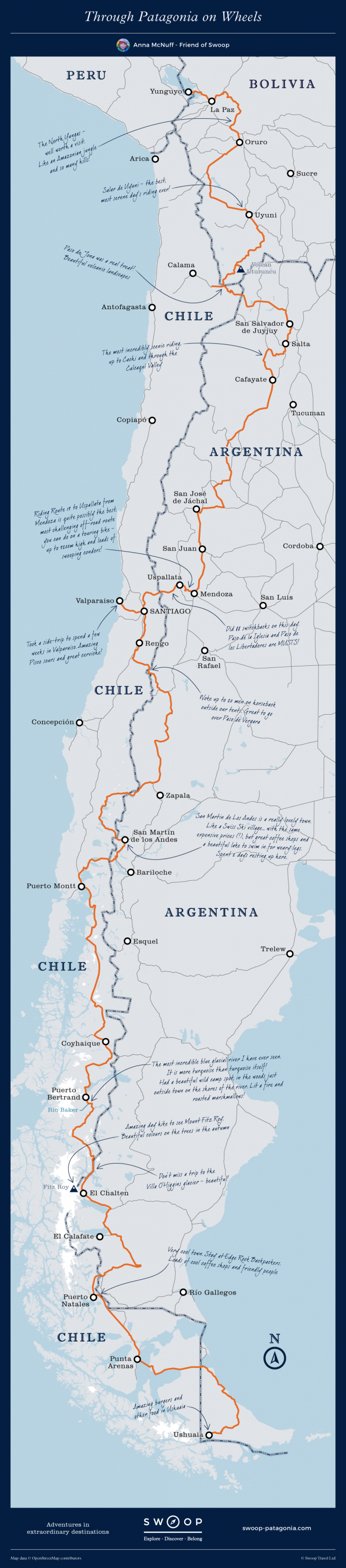

That day almost pushed us to the edge, but in reality it was just another day on the road in South America. In October of 2016, my friend Faye and I crash landed our ill-prepared British bodies into La Paz, Bolivia at 4,000 metres above sea level. From there we began a 9,000km, 6 month cycle south, on a mission to take on as many peaks and passes of the Andes mountains as possible along the way. When April 2017 came around, we arrived at ‘The end of the world’ in Ushuaia, having ascended over 100,000 metres on our humble bicycles.

We revelled in the vast volcanic landscapes of Bolivia, and equally in the serene ride across the Uyuni salt flats – with no sound beyond the crunch of our wheels as we broke, rhythmically, through the crusty edges of miles upon miles of hexagons made of salt. At Volcán Uturuncu, we ascended to 5,900 metres high before our bodies gave out and we began to run out of light. It wasn’t the full 6,000 metres we were aiming for, but to be perched on the side of a volcanic slope, and to have a 360 degree view of the surrounding red and black rock landscape entirely to ourselves – that was pure magic.

“There was no sound beyond the crunch of our wheels as we broke through the crusty edges of miles upon miles of hexagons made of salt.”

By far the greatest joy of a journey through the vastness of South America was that we were able to camp wherever we liked most nights, and each morning were greeted with a new and different view. Dappled sunlight on a forest floor, morning mist rising over a laguna, cacti perched precariously on red rocks, a glacier snaking down a granite peak. This was adventure travel at its very finest.

Our journey through Patagonia along the legendary Careterra Austral was a mixed affair, and I couldn’t help but feel that in many places there was more fun to be had off the bike rather than on it. I grew ever more envious of those with hiking boots and oversized packs – heading away from the roads and into the surrounding mountains. But when the rubble tracks quietened down in the evenings and the valleys were our own once more, we enjoyed many beautiful wild camp spots, including one next to the bluest glacial lake I have ever seen. We wound our way around the side of snow-capped mountains, following the path of peppermint coloured rivers into lush green forests and beyond.

“We encountered 50 mph cross-winds, one very nasty dog bite, -20c, running out of food and a bout of gastroenteritis.”

As is the yin yang of the universe, such highs came with great lows to balance them out. In many places we battled with slow progress on sandy and corrugated tracks. I even got a saddle sore so large and so angry that I named her Sally (Sally had her own pulse and didn’t take kindly to being bounced around on all day). We encountered 50 mph cross-winds, one very nasty dog bite, temperatures as low as -20c, running out of food and to place the cherry atop the challenge cake – a bout of gastroenteritis which left Faye in hospital on a drip. These are challenges that I won’t forget in a hurry, but equally ones I would never replace. No one tells a great story about the time everything went to plan, and as famed round the world motorcyclist Ted Simon says: ‘The interruptions are the journey.’

South America is a wild and stunning place, and as with anything truly wild, you cannot hope to tame her. The mystery and unpredictability of daily life there is part of the appeal, and ultimately the greatest source of beauty. In six months of travel, I have barely scratched the surface. I have left many corners unexplored, and many questions unanswered – but as with all things that we come to grow fond of in life – it is never really a goodbye. More just, a ‘so long for now’. South America, I miss you, but I’ll be back.

Anna’s Route: